baltakatei

/ˈbɑːltəkʊteɪ/. Knows some chemistry and piping stuff. TeXmacs user.

Website: reboil.com

Mastodon: baltakatei@twit.social

- 7 Posts

- 16 Comments

10·3 months ago

10·3 months agoOr authors could preëmptively declare their works to be in the public domain upon their death.

I wish Creative Commons had a license like that. Something like

CC PDD(Public-Domain-on-Death) which would activate upon the creator’s death, allowing them and publishers to freely monetize their work while they’re alive, but which would release the work into the public domain immediately after.It might even incentivize music and book publishers to get their artists health insurance. 😃

PLATO: An automobile is craft with an internal combustion engine, crankshaft, and wheels.

DIOGENES wheels in a HONDA GX630 PRESSURE WASHER

DIOGENES: Behold! An automobile!

1·3 months ago

1·3 months agodeleted by creator

“That all life beyond this planet never existed, no matter how irrationally improbable that may be.”

161·3 months ago

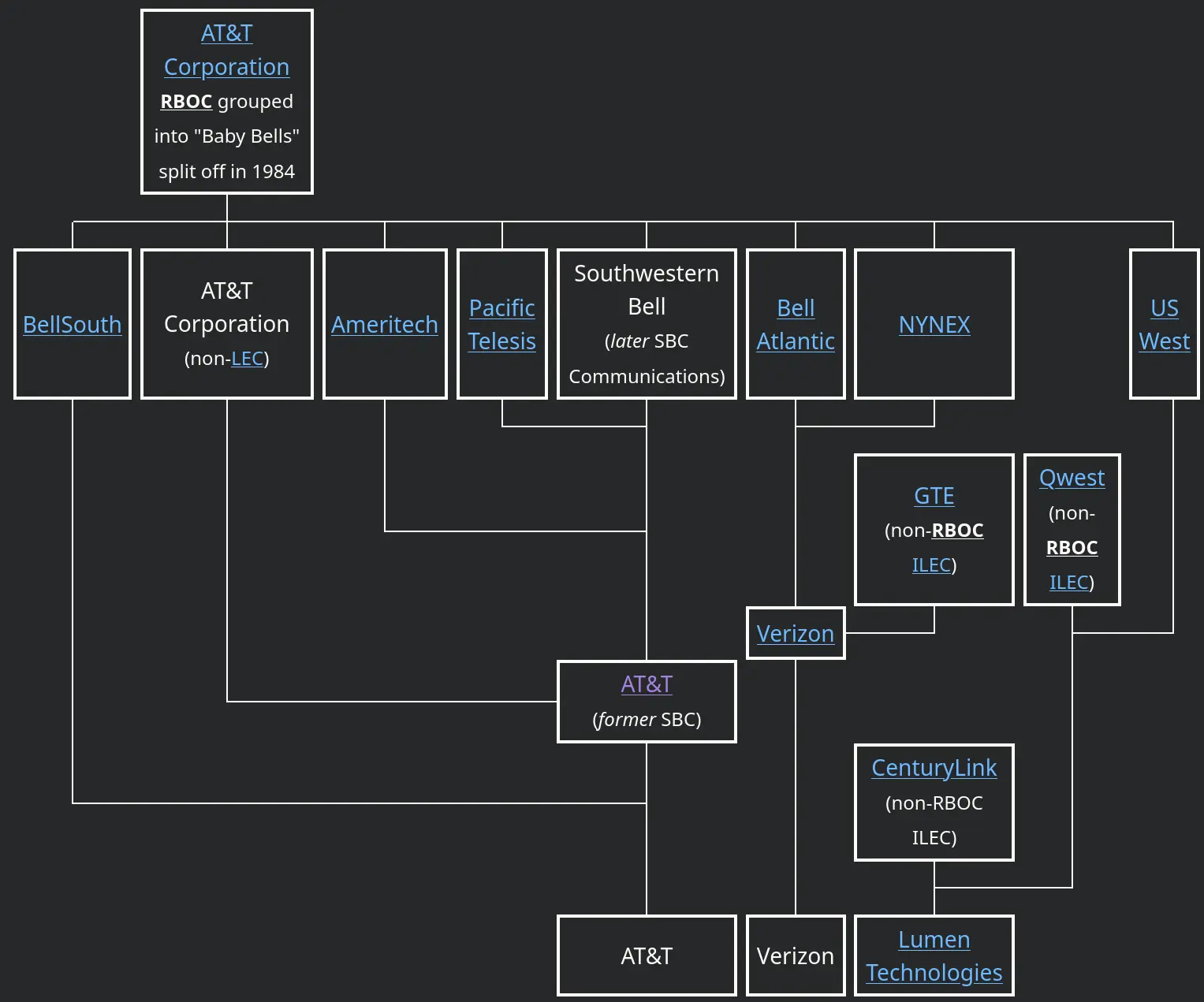

161·3 months agodon’t let them slowly re-consolidate in the following 20 years

I too remember how AT&T was broken up only for most of its Baby Bells to remerge back into Ma Bell.

To prevent this for future breakups, I say the content and services sold by big tech should be made competitively compatible and interoperable via nullification of DRM laws; people buy music and movies and cloud storage; let them legally move their purchases to any competitor and big tech companies will break up naturally as local competitors emerge from people who dislike big tech for their own reasons. Monopolies cannot be trusted to lower prices for content and services. Legally nullifying DRM is like the FCC telling customers in 1968 that it was finally okay to ignore the “Bell equipment only” legal warning that had kept them locked into leasing their telephone sets for usurious amounts from AT&T for decades. A few years later, in 1982, AT&T was broken up. AT&T is almost a total monopoly again, but phones remain interoperable.

If tech giants such as Google cannot be broken up, then their services should be required to be compatible and all data exportable to competitors. See the EFFʼs “Competitive Compatibility” concept. Buy a movie off Google’s YouTube but Google misbehaves? It must be exportable to a market competitor that you do support. Don’t like how Google handles your email? You should be able to switch your email address to a competitor just like you can change phone companies without losing your phone number.

Basically, if the US Federal government cannot discipline monopolies by breaking them up directly, they should break up the moats and walled gardens the monopolies built to keep customers locked in to maintain their monopolies. See Chokepoint Capitalism by Rebecca Giblin and Cory Doctorow.

Based on my cheatsheet, GNU Coreutils, sed, awk, ImageMagick, exiftool, jdupes, rsync, jq, par2, parallel, tar and xz utils are examples of commands that I frequently use but whose developers I don’t believe receive any significant cashflow despite the huge benefit they provide to software developers. The last one was basically taken over in by a nation-state hacking team until the subtle backdoor for OpenSSH was found in 2024-03 by some Microsoft guy not doing his assigned job.

Can’t wait for the day when Uncle Sam to turns brown.

2·3 months ago

2·3 months agoI used to think “chaos” had the same “ch” as “church” when I was a kid.

The chao of Sonic Adventure (1998)?

7·3 months ago

7·3 months agoThe one that wakes me up in the middle of the night is albeït. I thought it was fancy foreign speak pronounced “all bait”, but it is just a short form of “all be it”, is pronounced exactly like that, and is a synonym for “all though it be”.

In fact, electric vehicles have been common once before. In the early years of the twentieth century, there were three fundamentally different automobile technologies battling for supremacy, and electric cars held their own against competition from steam-and gasoline-powered alternatives, as they are mechanically much simpler and more reliable, as well as quiet and smokeless. In Chicago they even dominated the automobile market. At the peak of production of electric vehicles in 1912, 30,000 glided silently along the streets of the USA, and another 4,000 throughout Europe; in 1918 a fifth of Berlin’s motor taxis were electric.

The drawback of electric cars with their own onboard batteries (rather than trains or trolleys taking a continuous feed from a power line over the track) is that even a large, heavy set cannot store a great deal of energy, and once depleted the battery takes a long time to recharge. The maximum range of these early electric vehicles was around a hundred miles, (Ironically, about 100 miles is still the maximum range for modern electric cars: technological improvements in battery storage and electric motors have been perfectly offset by an increase in car size and weight, and drivers of electric vehicles suffer from “charge anxiety.”) but this is farther than a horse and in an urban setting is more than adequate. The solution is, rather than waiting for the battery to be recharged, you can simply pull into a station for a quick battery pack exchange: Manhattan successfully operated a fleet of electric cabs in 1900, with a central station that rapidly swapped depleted batteries for a fresh tray.

From The Knowledge (2014) by Lewis Dartnell, chapter 9 “Transport”. Cited works for the history of electric cars are:

- Crump, Thomas. 2001. A Brief History of Science: As Seen through the Development of Scientific Instruments. London: Constable & Robinson.

- Edgerton, David. 2007. The Shock of the Old: Technology and Global History Since 1900. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Brooks, Michael. 2009. “Electric Cars: Juiced Up and Ready to Go.” New Scientist, July 20: 42–45

- De Decker, Kris. 2010. “The Status Quo of Electric Cars: Better Batteries, Same Range.” Lowtech Magazine, May 3.

- Madrigal, Alexis. 2011. Powering the Dream: The History and Promise of Green Technology. Cambridge, MA: Da Capo Press.

17·4 months ago

17·4 months agoDrive out enough librarians and eventually youʼll find yourself needing to drive 4 hours to get a tool pulled or a melanoma whacked off since good dentists and doctors usually want decent schools with libraries for their kids.

9·4 months ago

9·4 months ago<blink><marquee>Under construction!</marquee></blink>

2·4 months ago

2·4 months agoJust, buy a new iPhone and Mac every two years.

2·4 months ago

2·4 months agoTermux, rsync and SSH.

Worked okay until I got overzealous and killed my battery from leaving Termux on for convenience.

2·4 months ago

2·4 months agoThe USB Type-C is useful for sharing files offline between smartphones while the USB Type-A is useful when you want to backup files to a PC at some point.

Madness.