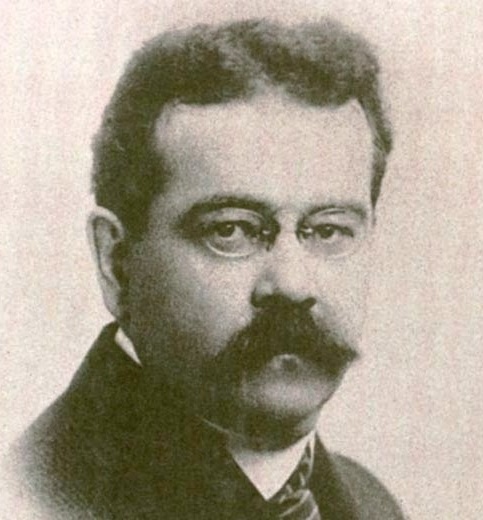

Activist Leo Igwe is at the forefront of efforts to help people accused of witchcraft in Nigeria, as it can destroy their lives - and even lead to them being lynched.

“I could no longer take it. You know, just staying around and seeing people being killed randomly,” Dr Igwe tells the BBC.

After completing his doctorate in religious studies in 2017 he was restless. He had written extensively about witchcraft and was frustrated that academia did not allow him to challenge the practice head on.

…

So Dr Igwe set up Advocacy For Alleged Witches, an organisation focussed on “using compassion, reason, and science to save lives of those affected by superstition”.

Dr Igwe’s prevention work also extends to Ghana, Kenya, Malawi and Zimbabwe and beyond.

One of the people the organisation has helped in Nigeria is 33-year-old Jude. In August, it intervened when he was accused and beaten in Benue State.

Jude, a glazier, who also works part-time in a bank, says he was on his way to work one morning, when he met a boy carrying two heavy jars of water which prompted him to comment on the boy’s physical agility.

The boy did not take the comments kindly, but he went on his way.

Later, Jude was followed by a mob of about 15 people throwing stones at him. Among them was the boy he had greeted earlier.

“Young men started fighting me as well, trying to set me ablaze,” Jude says.

He was accused of causing the disappearance of the boy’s penis through witchcraft, an accusation that shocked him and is untrue.

Claims of manhood disappearances are not uncommon in some parts of West Africa.

It is a claim that has been linked to Koro syndrome, a mental illness otherwise known as missing or genital retraction hysteria.

It is a psychiatric disorder characterised by an intense and irrational fear of the genital organs going missing or retracting into the body of the victim.